NEWS

Frank Lloyd Wright in Indiana

Exploring famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy in Indiana, where seven of his designs remain.

Master Class

Is there a more famous American architect than Frank Lloyd Wright? His work, eventful life, and outsized personality have inspired architectural acolytes, documentaries, films, novels, and everything from furniture to finger puppets. Born in 1867 in Wisconsin, his career spanned seven decades, during which he produced 1,114 architectural designs, 532 of which were built. Seven Wright-designed houses remain in Indiana.

The earliest of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs in Indiana, the 1906 DeRhodes House in South Bend illustrates the architect’s take on the Prairie style, with bands of art glass windows under the eaves of a low-hipped roof. Photo by John Clouse.

As America came out of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Wright saw the urgent need for affordable, well-designed houses for middle-class families. He created designs he labeled Usonian – a play on United States of North America – that he touted as the realization of a democratic, organic, uniquely American brand of architecture. Rooted in his Prairie design principles, Usonian houses possess a similar horizontality, with flatter rooflines, built-in furniture, less expensive windows (no art glass, for example), and carports instead of garages.

Five of Indiana’s Wright-designed houses are Usonians, from the 1939 tri-level Andrew Armstrong House in Ogden Dunes to the John and Catherine Christian House in West Lafayette, completed in 1956. Wright believed that the Usonian house should take into account the needs of the family it served, with back-and-forth communication common between the architect and the owner.

Herman Mossberg had admired Wright’s Robie House in Chicago and seen the architect’s reputation grow with his design of Fallingwater in Pennsylvania. When Mossberg wrote Wright asking if he could recommend a former student to design a home for him in South Bend, Wright replied, “Why have an imitation when you can have the original?” The red brick house commissioned in 1948 includes a two-story living area with mezzanine to make the home look two stories, a neighborhood building code requirement.

Democratic Design

Marion native Dr. Richard Davis met the architect in 1950 at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, while he was assisting on Wright’s gallbladder surgery. Taking Wright up on his offer to design a home for them, Richard and Elaine Davis visited the Mossberg House for ideas. They chose a wooded lot in Davis’s hometown, where the doctor was returning to family practice.

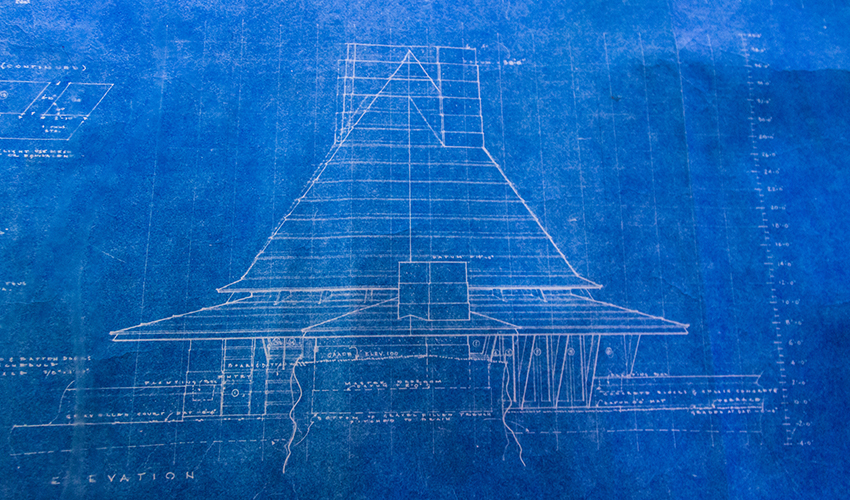

Wright, who frequently bestowed names on his houses inspired by the environment they occupy, called the Davises’ place Woodside. Wings extend out from a central hexagonal core that resembles a tepee, an arrangement drawn from an unrealized design Wright had planned for a Lake Tahoe resort. Built in tidewater cypress, with concrete block masonry walls and poured concrete floors colored red by the addition of an iron oxide compound, the house reflected the architect’s commitment to simple, affordable materials in his Usonian designs. Wright also designed a guest house and dog house for the family’s Saint Bernard, and later the main house’s addition.

For the Davis Home in Marion, Frank Lloyd Wright drew on the Midwest setting as well as a design he had created for a Lake Tahoe resort. Photo by davelandweb.com

The Davis House features a teepee-like core, with the living area taking up half the hexagon. Photo by Dave Wegiel, davewegielphoto.net.

Matthew Harris, the current owner, admired the home in his youth, when he used to drive by Woodside to visit a friend the neighborhood. When it came up for sale, he didn’t hesitate. The sixth owner, Harris has occupied the house for 21 years, during which time he’s connected with members of the Davis family. He opens Woodside for Wright devotees, and rents the property for overnight stays to allow fans the full experience of a Wright design.

“It took me quite a few years to get the furniture I thought would look right,” says Harris. “Generally I’ve tried to make as little change as possible, trying to keep the property up in a style I think Wright would appreciate.”

John and Dorothy Haynes commissioned one of Wright’s smaller Usonian designs, a 1,350 square-foot residence finished in 1952 in Fort Wayne. Small but efficient, the design incorporated built-ins throughout, and used varying ceiling heights to create visual interest, with the central living space dominated by cantilevered brick fireplace. “It was a delightful house to live in,” says architect and former owner John Shoaff, who recalls whiling away afternoons reading in the music room, which afforded views in two directions. “The fireplace was a bit of a mystery to me. It defied understanding how that thing stood.”

The Haynes House made national headlines in recent years as the current owner sought to have its local historic designation removed. Fort Wayne’s City Council denied the request, a decision supported by Indiana Landmarks and local preservation organization ARCH.

Winged Seed Takes Root

The Christian House in West Lafayette, the last of Wright’s Indiana commissions, may be the most fully executed expression of his Usonian ideals. After marrying in 1948, John and Catherine Christian wanted a modern residence for their first home and decided no one but Wright would do as architect.

Visiting him at Taliesin, Catherine prepared a 28-page booklet, “What We Need for How We Live,” detailing their space needs and how they would use each room, from family gatherings to faculty parties (Dr. Christian was a Bionucleonics professor at nearby Purdue). Stressing that they were on a budget, the couple struck a bargain with Wright: they would build it and over time would implement every aspect of his design.

After four years of communication, the Christians received finished plans in 1954 and completed the building in 1956. Wright called the house Samara after the winged seeds produced by the site’s evergreens. He repeated an abstract version of the winged seed design motif in the home and furnishings. Wright offered direction on everything from the furniture and china to the toilet paper holder. After Dr. Christian retired in 1989, he concentrated on finishing the details, including having the copper fascia fabricated that Wright had designed for the roofline. The last furnishings commissioned by Dr. Christian before he died in 2015—linens, bed runners, and a table runner—are currently being fabricated.

Samara’s landscaping reflects the plan dictated by Wright, a rarity for Usonian homes. The completeness of the property’s design earned Samara recognition as a National Historic Landmark in 2015. “I find it amazing and admirable that the Christians worked throughout their lives to fulfill their promise to Wright,” says associate curator Linda Eales. Although their daughter Linda Christian Davis lives in Texas, she and Indiana Landmarks’ Marsh Davis and others on the board of the Christian Trust oversee the property today.

It’s a collaboration worth seeing. Make plans to visit Samara when it opens for tours in April; reservations can be made by calling 765-409-5522 or on Samara’s website, samara-house.org.

For more on Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy in Indiana, read the March/April issue of Indiana Preservation.

Stay up to date on the latest news, stories, and events from Indiana Landmarks, around the state or in your area.