NEWS

Identifying Indiana’s Pattern Book Architecture

With detailed illustrations, floor plans, and essays on design, pattern books spurred the construction of houses in the nineteenth century.

Book Smart

For hundreds of years, architects have printed books of their work. Some of the earliest date to the 1500s, when Italian architect Andrea Palladio created a series of publications featuring his classically inspired designs. His work went on to influence fashionable architecture across Europe and beyond for centuries to come.

From the time Indiana became a state in 1816, local carpenters and builders could take inspiration from a variety of pattern books circulated by American architects. Early pattern books served more as technical builders’ guides, but architectural publications aimed at middle-class consumers didn’t become common until the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1840s, new publications featured detailed illustrations, floor plans, and essays by architects promoting their designs as the answer to gracious living.

While wealthy families might commission entire houses from pattern book designs, more often builders incorporated specific details like entrances, bargeboards, and mantels.

Crawfordsville’s 1854 Ramey-Milligan House includes bargeboard and window details that resemble designs published by architect Samuel Sloan in 1852.

It takes a trained eye to spot pattern book houses. Unlike prefabricated and mail-order kit homes of the twentieth century that could be shipped for on-site assembly, the builders of pattern book houses often mixed and matched elements from various designs. And in the intervening decades since their construction, some of these details may have been lost or altered beyond recognition.

Among old-house enthusiasts, pattern book houses have developed something of a cult following, as homeowners and restoration specialists seek clues that will help recreate lost features or make sense of later alterations.

Researchers once had to travel to libraries with architectural archives or track down reprints of pattern books to look for connected designs, but the digitization of many such publications in recent years has helped streamline study. Passionate followers of pattern book architects such as William Barber and D.S. Hopkins even share their expertise on social media, helping homeowners identify designs that match up with their historic residences.

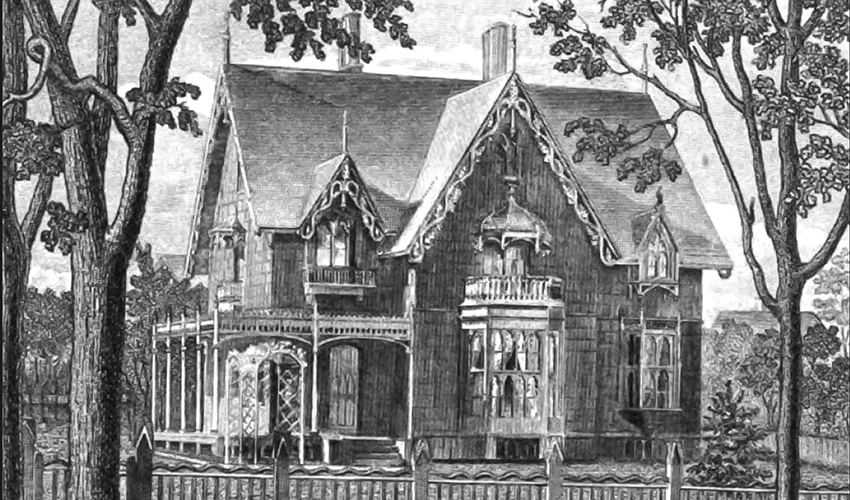

A fan of architect’s George Barber’s pattern book designs alerted Tabetha Heemstra that the Rensselaer house she is restoring (above) came from Barber’s Cottage Souvenir No. 2. Heemstra is chronicling the restoration journey of her “McKinley Manor” on social media. (Photo courtesy Tabetha Heemstra)

Progress in technology and transportation in the mid-1800s helped speed dissemination of pattern book houses in Indiana. Printing advances made pattern books and illustrated magazines more affordable, and the opening of the Wabash & Erie Canal in 1843 and expansion of the railroads in the 1850s provided pipelines for transporting publications, building materials, and skilled craftspeople from the East.

Around the same time, landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) collaborated with architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-1892) to publish two books: Cottage Residences (1842) and The Architecture of Country Houses (1850). Along with sharing his own house designs and examples by other architects, Downing’s publications offered advice on every aspect related to each house’s construction—from paint choices and furnishings to landscape plantings and more. His gardening magazine, The Horticulturist, also published house designs.

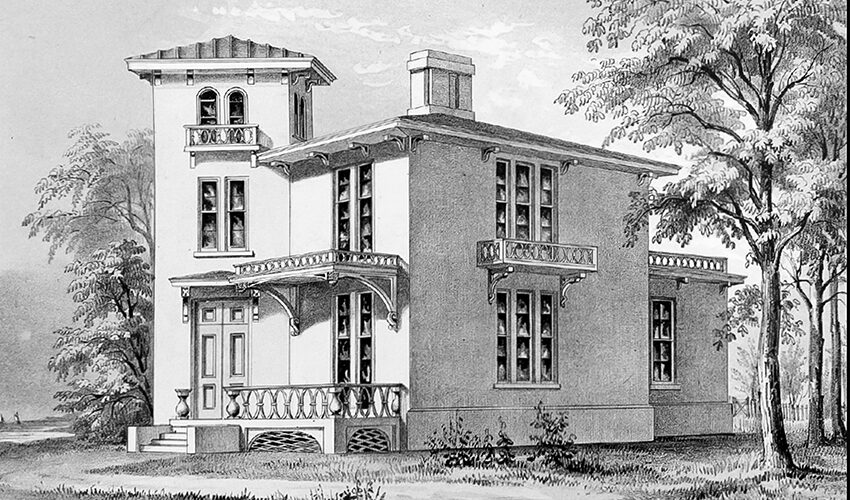

Downing’s books have long been cited as the design inspiration for the Gothic Revival-style Fowler House in Lafayette, built beginning in 1851 for wealthy merchant Moses Fowler and wife Eliza. More recent research revealed that the house’s floor plans and exterior follow “Freestone Cottage” in Middletown, Connecticut, a design featured in the April 1851 issue of The Horticulturist (pictured below, illustration courtesy archive.org).

“Fowler must have been impressed with this design, because he began construction of a house based on it one month after it appeared in the magazine,” says Benjamin L. Ross, architectural historian and Lafayette native, whose visit to the Fowler House as a kindergartener inspired his adult research into pattern book houses.

Ross notes that the verandas, chimneys, and windows of the Fowler House show similarities to designs in Downing’s The Architecture of Country Houses, while interior plasterwork and woodwork follow designs in David Henry Arnot’s Gothic Architecture Applied to Modern Residences printed in 1850.

“Rather than simply copying a single pattern-book source, the Fowler House’s builders combined elements from several current publications to create a unified whole,” adds Ross. “These three design sources show the range of architectural publications in use by 1852 and the ability of Hoosier builders to follow the latest New York fashions.”

Ross has identified houses throughout the Wabash Valley that drew elements popularized by other well-known pattern book architects of the period. Williamsport’s 1855 Hitchens House is an identical twin to the 1855 Kent House built next door and later demolished—both drawn from The Architect, Vol. II published in 1847 by architect William Ranlett (1806-1865).

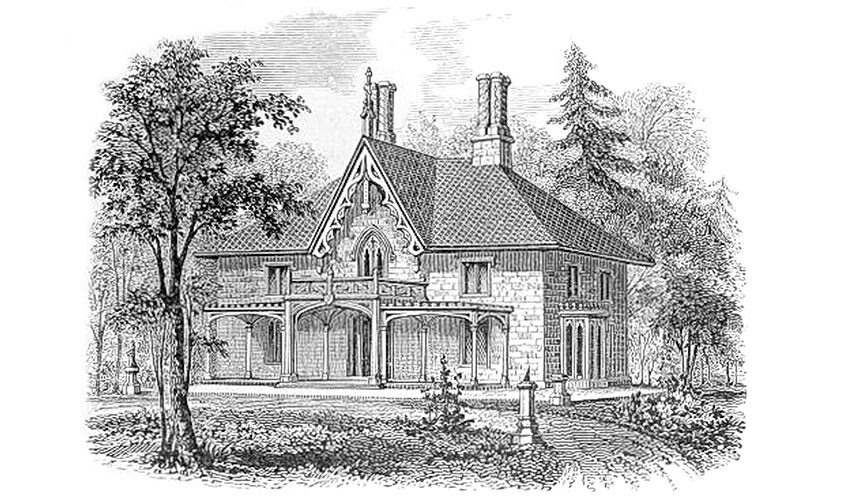

Philadelphia architect Samuel Sloan (1815-1884) popularized Gothic Revival and Italianate-style dwellings in his book, The Model Architect, first published in 1852. Gothic Revival windows and bargeboards on Crawfordsville’s 1854 Ramey-Milligan House match details published by Sloan. Brothers William and James Banes arrived in New Albany in the 1850s and took inspiration from Sloan’s designs to build houses over a span of 50 years. Their works typically exhibited front-facing gables—often incorporating bay windows—along with a side wing. Brackets in the eaves and elaborate porches were staple features in some of the more high-style examples.

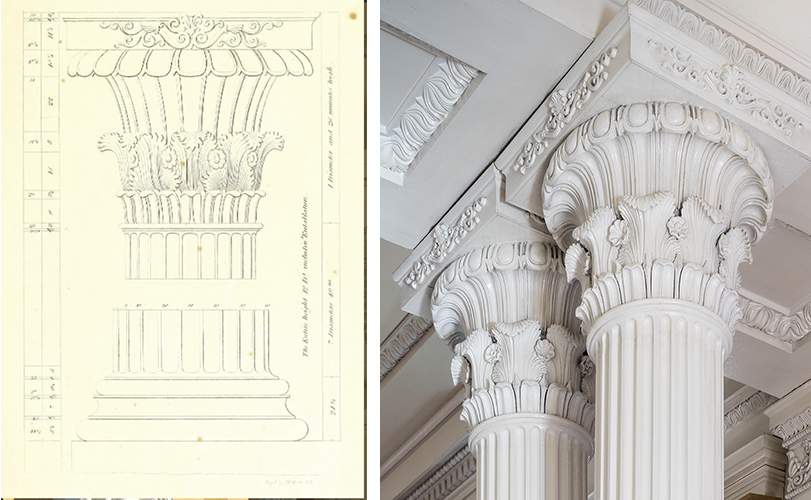

Indiana architects also drew inspiration from pattern books. Column capitals, moldings, architraves, and other details from Minard Lafever’s The Beauties of Modern Architecture (1839) appear in three notable landmarks in Madison: the 1844 J.F.D Lanier House and 1849 Shrewsbury-Windle House by Francis Costigan, and in the 1849 Washington Fire Co. No. 2 by Matthew Temperly. “Using these design sources doesn’t mean these architects weren’t talented and creative,” says Ross. “It was how they learned the latest fashions. Costigan was particularly skilled at combining pattern book details in his high-style designs.”

Indiana architect Francis Costigan incorporated a column capital illustrated in Mindard Lafever’s “The Beauties of Modern Architecture” in his design of the 1849 Shrewsbury-Windle House. (Photo: Susan Fleck Photography; illustration from archive.org)

So how do historic homeowners discover if their houses include elements from nineteenth-century pattern books? Peruse publications printed around the time of the house’s construction and look for nearby house “twins” that may have already had their provenance documented. A good place to start is the digitized collection of pattern books at archive.org, particularly in the Association for Preservation Technology’s Building Technology Heritage Library, or contact the Indiana Landmarks regional office nearest you.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of Indiana Landmarks’ member magazine, Indiana Preservation.

Stay up to date on the latest news, stories, and events from Indiana Landmarks, around the state or in your area.