Uncovering the history of a house can be a lot like detective work. Where do you even begin?

You’re intrigued by an old house and you want to know its story: when it was built, who lived there, how it may have changed over time. Or maybe your ambition is even broader: You want to learn about its architectural style and the development of the entire neighborhood.

You need to become an old-house detective.

Historic house research is a lot like detective work. You’ll need patience, perseverance, and time. Luck also helps. The story of a house builds as you follow leads, cross-check facts and track down sources to learn about the owners, architects, and builders. The work may take you to the Internet, libraries, city and county offices, historical societies—perhaps even on scouting trips to meet descendants of former owners. If your curiosity is deep, you may be able to build a fascinating house biography.

What follows are some general research recommendations. Organization of records and the availability of materials varies by county. When in doubt, consult experts in local history and ask questions.

Don’t Reinvent the Wheel

It’s very possible that a lot of the old-house information you want has already been compiled. Check first for files in the local history collection of your community’s library, county museum, or historical society, particularly if a prominent family built your house. The Internet may yield photographs, newspaper stories, for-sale ads, and biographical information on former owners.

If the house is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, it has already been researched through the nomination process. For a list of National Register properties, consult the National Park Service Focus database or the State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD) and SHAARD GIS maintained by the state’s Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA).

You can also check with DHPA or Indiana Landmarks to find out if an architectural survey of your county has been completed for the Indiana Historic Sites and Structures Inventory. All 92 counties have been surveyed, with results either published in print catalogs or available in SHAARD.

Local libraries may also have a copy of the survey findings, called an Interim Report. While this report typically includes only basic information on a property, it will provide an approximate date of construction and may also offer helpful historical background. SHAARD and SHAARD GIS may contain additional information and photographs.

If the house is in a locally designated historic district, the preservation commission may have historical information about the building. To learn if there is a preservation commission or historic review board in your community, contact your nearest Indiana Landmarks regional office or the Indiana Preservation Directory.

If a very rough range of construction dates would satisfy your interest, a basic physical examination of the house and a brief study of its architectural style might provide the answer you seek. (See Using Structural Clues for helpful resources on recognizing architectural styles.) You can generally arrive at a 10- to 30-year range for the construction date of a house by recognizing the style and checking reference works to determine the period of that style’s popularity in the region. If you don’t already know the year your house was built, narrowing the window in this manner will save research time in legal documents, city directories, and other sources.

Using Legal Documents

If you want to know more than the architectural style and a rough construction date for the house you’re researching, consulting legal documents will allow you to develop the chain of title: a list of owners of the property from the patentee (original purchaser from the U.S. government) to the present. You may be fortunate to find an abstract for your house. If not, you will have to conduct deed research to establish the chain of title.

Although the activity recorded in an abstract, and the information you’ll find if you pursue deed research, refers to the land rather than the structure, these documents will reveal the names of owners and details that will help in dating your house. Mortgages, probate records, and liens often give concrete facts about the house and lead to other sources of information.

The Bureau of Land Management has an online database with patentee information for most of Indiana. These records indicate the original transfer of land from the federal government to an individual but do not provide building construction dates.

Some Concrete Advice About Abstracts

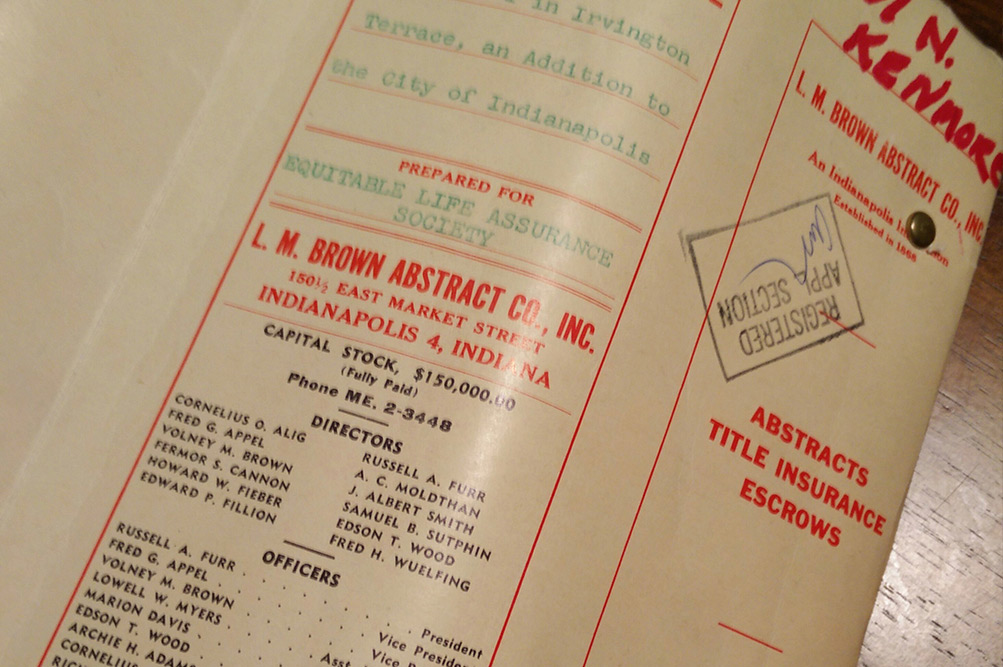

Most parcels of land have been the subject of legal transactions, which means you can look for an abstract: a summary of deeds, wills, mortgages, tax sales, probate proceedings, litigation, and other transactions that have affected a particular property. Abstract companies—forerunners to today’s title insurance firms—prepared these documents to certify that sellers held clear and valid title before a sale.

An abstract generally contains the date and names of people or businesses involved in each property transaction, type of transaction, and reference numbers for the original record (the estate docket number, for example, in a probate court case, or the warranty deed record and page number entered at the time of a sale). You may get lucky and find an abstract in your house; look in cupboards, attic and basement rafters, and any collections of previous owners. If you have an abstract, you won’t have to conduct deed research.

The transactions detailed in an abstract refer to land rather than structures, so it’s not likely to tell you the date of your home’s construction. Instead, you will have to interpret, infer, and follow leads offered by the abstract to other potential sources of that information. For example, a leap in the value of a property between consecutive sales might suggest a capital improvement, such as the construction of a house on the property. This is by no means a foolproof assumption—inflation or reassessment could have caused the increase—but you can confirm it using other sources such as city directories, newspaper articles or ads, historic maps, and photographs. Mortgages and mechanic’s liens might also signal the construction of a house.

Passing the Abstract

An abstract—generally a thick sheaf of papers joined with metal fasteners and folded into a thick roll—may be passed from one owner to the next at closing, or you may find one in the house or collection of a former owner.

Doing the Deed Research

If you are unable to locate an abstract, deed research will allow you to build the chain of title. To begin tracing the chain, you’ll need the legal description of the property and the name of the current owner. The legal description is different from the mailing address and includes references to a section, township, and range. In the case of urban properties, the legal description usually also includes a subdivision name and lot number.

For example, the legal description for the Kemper House in Indianapolis is Roache’s First Addition, 53’8” North Side Lot 5. The legal description for the Huddleston Farmhouse, a rural property on the edge of Cambridge City, is the northeast quarter of Section 28 in Township 16 North Range 12 East, abbreviated as Pt NE¼ S28 T16N R12E.

If you don’t know the legal description and current owner’s name, contact the county or township assessor’s office. Many assessors offer this information via the web. For example, in Indianapolis, legal descriptions may be obtained at http://maps.indy.gov/AssessorPropertyCards/.

Armed with the legal description and name of the current owner, you can begin the process of deed research in the county auditor’s and recorder’s offices or the Indiana State Library, located in Indianapolis. The State Library has copies of most county deed indexes and even some county deed books. To save time and frustration, find a helpful staff member or someone in your county who has conducted such research and can offer directions, introductions, guidance, and shortcuts on the process.

In large metropolitan areas where it may be difficult to access historic records in a government office, it may be possible to conduct deed research through a private title company (for a fee). You might also hire a freelance historian to help with research. Contact Indiana Landmarks’ library for a list of consultants.

Organization and availability of records vary by county. But essentially, to build the chain of title or ownership history, you trace backward in time, beginning with the current owner, using transfer books in the assessor’s office.

Deeds—the proof of property ownership—are organized by grantee (the recipient of the property or buyer) and grantor (disposer of property or seller) in transfer books. Check with the county assessor to find out if any of their records are available through a computerized database. If so, these records may get you back into the 1960s or earlier.

Start your search with the earliest owner’s name in the transfer book corresponding to ownership date. He or she will be listed as a grantee. (You will note that the alphabetical order in these books may be loose—all of the “As” might be together, but they may not be alphabetized.) The grantor’s name will also be listed, along with the value of the land and improvements (buildings). As you proceed, be sure to keep complete notes on each transaction and make sure the legal description matches the one for your property.

Repeat the process using the previous owner’s name. Remember, the grantor of the deed you are looking up is the grantee in the preceding sale.

Once you’ve constructed the chain of title through the transfer books, more specific information may be obtained through the grantor/grantee indexes in the recorder’s office.

Check the last name of a grantee in the grantee index that corresponds to the year identified in the transfer book. Here you will find the type of transaction, the book and page number for the actual deed, the amount of the transaction, and the date it was signed. In each case, check to verify that the legal description refers to the property you are researching, since many people have owned and sold several lots in their lifetimes. Transaction amounts shown on deeds, as in an abstract, may offer clues to construction; a large increase in property value may indicate the building of a house or an addition.

Consult the deed book and page number referenced in the index for more detail. In addition to property owners’ names and amounts of sale or consideration, the deed may provide birth, marriage, divorce, or death dates of owners and associated individuals and, in some cases, lists of household contents or other tangible assets, as well as information about buildings on the property. Deeds will also record restrictive covenants and easements.

Watch in the grantor/grantee indexes for special deeds, such as mortgages and references to court records, mechanic’s liens, and other encumbrances including leases and tax delinquencies—all of which may be filed separately from warranty deeds. Since a mortgage is an owner’s means of raising money, it may signal a construction project: the building of a new house or a remodeling.

Mechanic’s liens—claims filed by construction contractors for unpaid bills—may also be filed separately from the deeds. Since they indicate building activity, these records are worth tracing; they may describe the construction project, and even detail materials and products, in addition to listing the names of builders or craftsmen and the amount of the claim. Court records referred to in the grantor/grantee index are also significant sources of house information. Lawsuits, wills and probate proceedings, divorce, and mental illness cases may contain relevant descriptions of the house and its contents.

Although their availability varies greatly from county to county and city to city, tax records and building permits are public documents that may yield information of interest. Check with the assessor and permit agency in your county to find out about access to these records. Many newspapers also contained a weekly listing of building permits, so check to see if this was a regular feature in your community.

Searching Historical Documents

Libraries and historical societies at the local, county, and state levels are fertile sources for historic house research. City directories, old newspapers, fire insurance maps, volumes of biographical sketches, corporate and club histories, photographs, and memoirs can put flesh on the skeleton developed through deed research.

Consulting City Directories

City directories are an easy source to consult for the names of a home’s occupants (as opposed to owners), as well as approximate construction dates. These directories typically also give the principal resident’s occupation. Published for cities of various sizes, the directories were inaugurated in some towns as early as 1855.

If you have completed a chain of title, compare the names on the title to the city directories. From 1914 forward, most Indiana city directories contain an index by street address as well as occupant’s name. If you don’t know the names, research in pre-1914 directories becomes a tedious hunt through column after column of names as you search for your address. However, online, digitized versions can save you time if they allow you to search for names and addresses.

Be aware that street names and numbering systems may have changed; in Indianapolis, for example, addresses changed in 1887, 1899, and 1916. Keep in mind, too, that directories do not provide up-to-the-minute data: Their publication schedules often create a one- to two-year lag in information. For example, if your address does not appear in directories until 1921, the house might have been built between 1918 and 1921.

Be cautious if a structure is continuously listed at your address from a much earlier date than your home’s probable construction date. In such a case, consider the possibility that an earlier structure on the site was demolished or otherwise lost, making way for the building of your house.

Directories frequently contain spelling and other mistakes, so confirm your research with other sources. You can generally find city directories at your local library, or in the Indiana State Library. See the “Helpful Links” section for access to digitized city directories.

Going Down the Road with Insurance Maps and Atlases

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, publishing companies began issuing maps and atlases of American cities and towns to assist the fire insurance underwriting industry in establishing rates. The Sanborn Map Company of New York grew to dominate the field. Depicting building outlines and color-coded to indicate materials, the periodically updated maps and atlases served the underwriting industry until after World War II.

Sanborn maps representing the period from about 1883 to 1955 are generally available for Indiana cities. By comparing maps produced over a series of years, you may note alterations in your house and outbuildings, new construction, and neighborhood development. Sanborn maps in the public domain (published before 1923) are accessible through the Indiana Spatial Data Portal. Maps published after 1923 are available on microfilm at many public libraries and historical societies and through paid subscriptions at some larger libraries, especially at universities. For an explanation of the symbols used on Sanborn maps, consult the Library of Congress collection.

Baist Atlases, also produced for fire insurance purposes, include similar maps drawn on a smaller scale. Consult a local library or the Indiana State Library for original or microfilm copies. Check Indiana Memory for digitized maps.

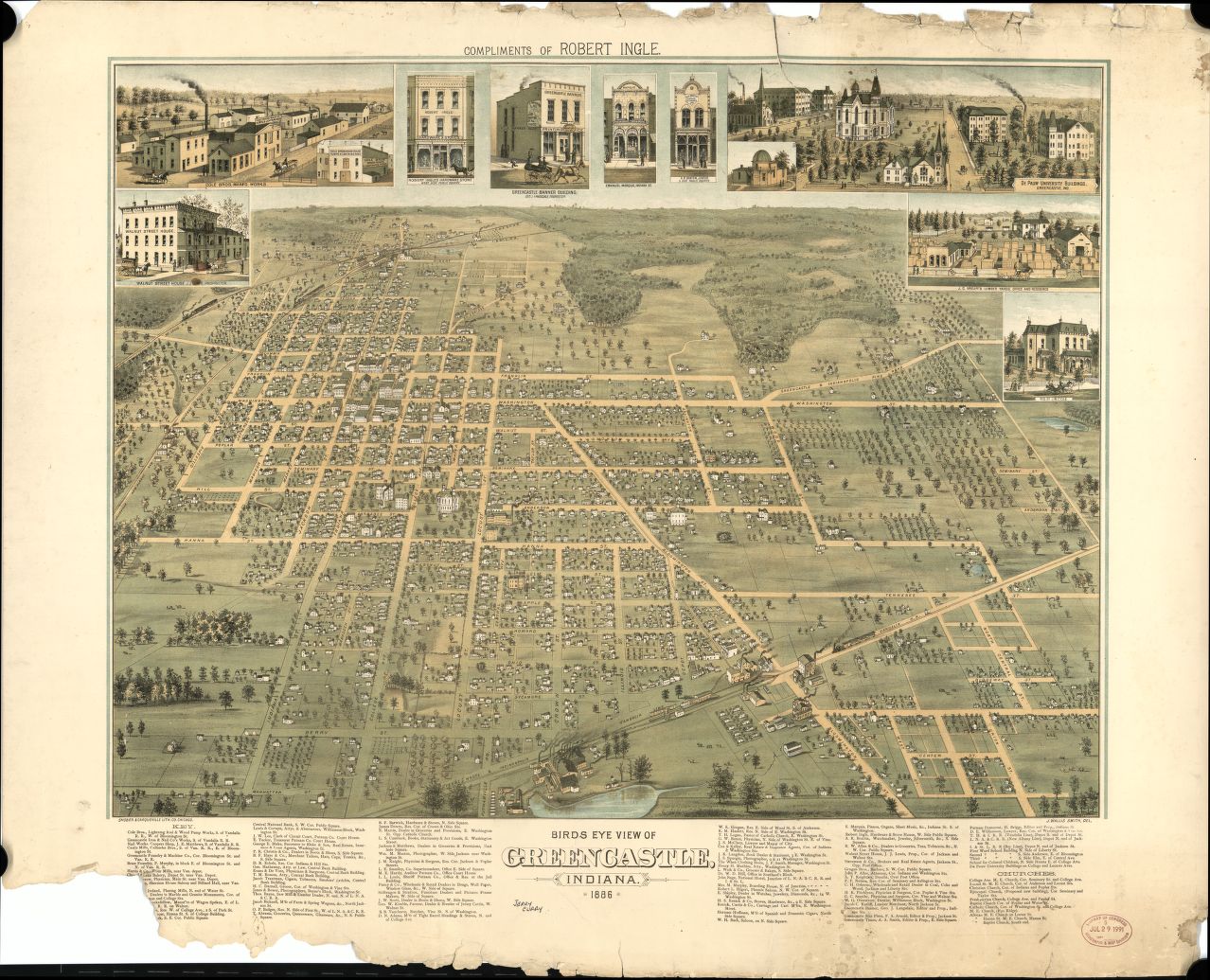

Scanning Aerial Views and County Atlases

Aerial or bird’s-eye views were popular in the nineteenth century for large and small communities. Although neither as common nor as frequently issued as fire insurance maps, aerial views are valuable for their scope and detail. They show buildings and outbuildings in three-dimensional perspective and offer valuable evidence of building relationships and major landscape features, such as orchards and wooded areas.

In his authoritative reference work Views and Viewmakers of Urban America (University of Missouri Press, 1984), John Reps documented aerial views of the following Indiana communities: Anderson, Attica, Auburn, Cambridge City, Columbus, Crawfordsville, Delphi, Elkhart, Evansville, Fort Wayne, Frankfort, Greencastle, Greensburg, Indianapolis, Kokomo, LaPorte, Lafayette, Logansport, Madison, Michigan City, Mishawaka, Muncie, New Albany, New Castle, New Harmony, Peru, Richmond, Seymour, Shelbyville, South Bend, and Terre Haute. Some of these aerial views are in the digital map collection of the Library of Congress, and at Indiana Memory, while others may be found in the collections of local libraries and historical societies.

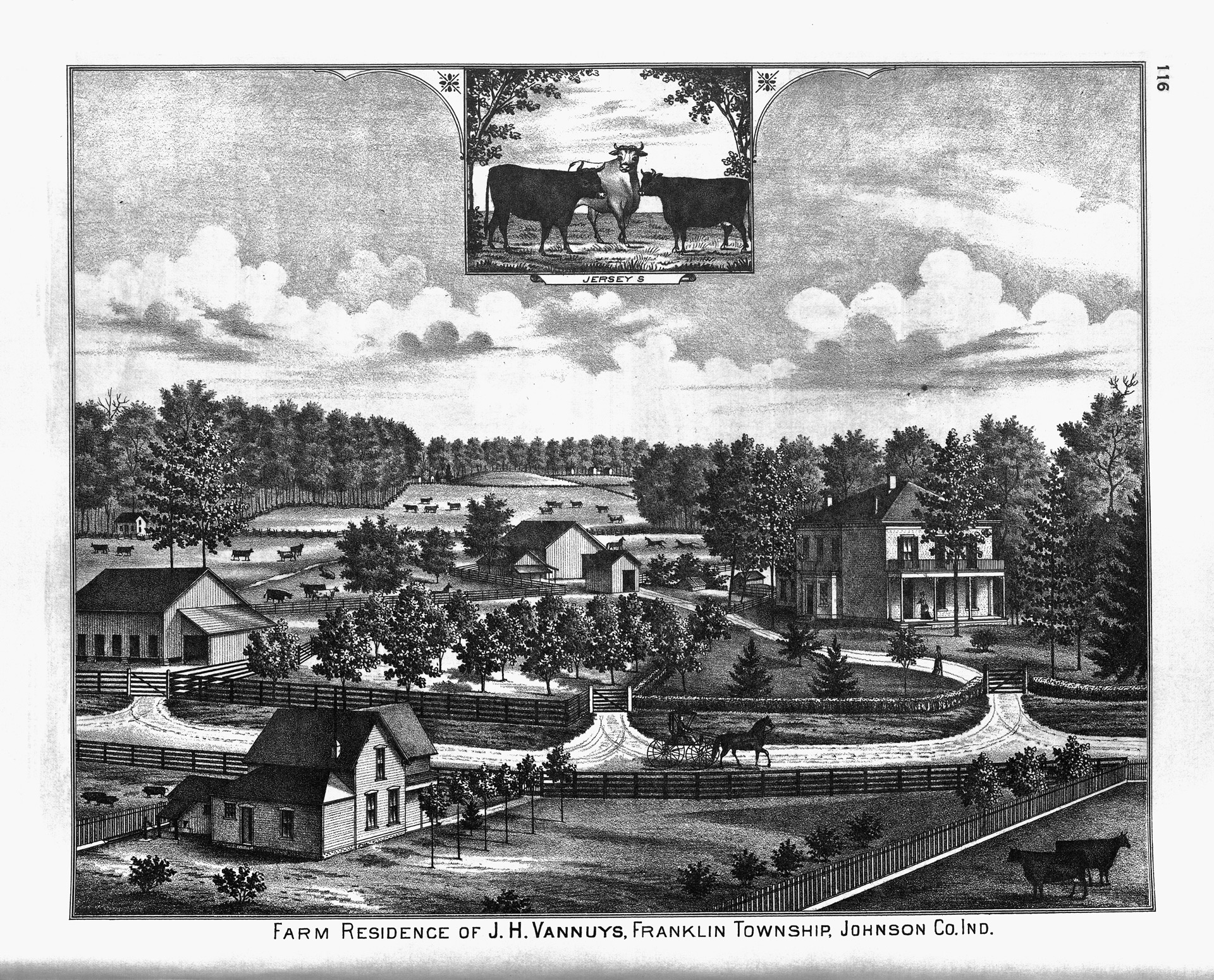

County atlases from the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries are also valuable sources for historic house research, particularly if your home is in a rural area. These atlases contain maps of the county’s townships drawn to indicate land ownership and usually show the position of residences on the lots, along with the name of each parcel’s current owner and the amount of his or her acreage. Maps of the county’s larger cities may be included, but they do not usually provide the names of property owners.

Most of the atlases contain renderings of prominent farmsteads, sometimes inset with portraits of the owners. If the subject of your research is a farmhouse, an atlas may provide an owner’s name, help you narrow down the construction date, note whether the house has been moved—not an uncommon occurrence in rural areas—and perhaps even show what it looked like.

Many of these oversized publications also offer histories of the county, the townships, major local institutions, and professions, along with biographical sketches of citizens and business directories. The atlases were, in general, published in the 1870s and 1880s; in some cases, an update was produced early in the twentieth century. In recent years, many of these early atlases have been reprinted by historical societies and may be available for purchase or online. Look for county atlases in your local library or historical society or at the Indiana State Library. Digital copies may be found through Indiana Memory.

Considering County Histories

You may find information about early owners of your property in a volume of county history. Like atlases, county histories were generally first published in the 1880s, with updates in the early twentieth century. The WPA Writers’ Project compiled an index of each county history, a helpful tool if you’re looking for references to a specific family. In addition to having a copy of the county history, your local library may have vertical files containing pamphlets, news clippings, and brochures on historic houses. Tell the librarian about your project and ask for help in using the library’s resources to the fullest extent in conducting your research. In addition, Google Books and Internet Archive have digitized some Indiana county histories.

Perusing Newspapers

Most local libraries maintain copies of historic newspapers; many are on microfilm, and the number of digitally available copies is growing rapidly. If your local library does not have old newspapers, consult the Newspaper Section of the Indiana State Library, whose holdings include approximately 4,000 titles representing 500 communities. This website also links to “Hoosier Chronicles,” the state’s digital newspaper program. Very few of these old newspapers are indexed; however, digital copies are searchable.

Digitized papers use optical character recognition (OCR). The computer reads only what appears on the printed page. Therefore, use broad search terms and be aware of abbreviations. For example, if you use the search term “Penn,” OCR will not highlight “Pennsylvania.”

OCR is also limited to the quality of the original copy. If the original is blurry, damaged, or uses small print, it may not provide accurate search results.

Be sure to use dates determined from other sources such as property records, city directories, and biographical resources to narrow newspaper searches. If you know when an early owner died, for example, look for the obituary; nineteenth and early-twentieth century obituaries are often lengthy accounts, offering much more information than today’s brief notices. You might search for wedding announcements, which often include detailed descriptions of interior decoration.

If the house belonged to prominent people, or is located in what was originally an affluent neighborhood, the newspaper might have run a feature article on the home’s architecture and décor. In larger cities with daily newspapers, such features might have appeared in a “House and Garden” or “Real Estate” section of the Sunday paper. Such newspaper articles form the basis of Old Houses in Indiana, a three-volume work in the Indiana State Library compiled from features written by Agnes McCulloch Hanna between 1929 and 1932 for The Indianapolis Star. These articles, along with images from Wilbur Peat’s Indiana Houses of the Nineteenth Century, are available online through the IUPUI University Library digital collections.

Photo credit: Joan Hostetler, Heritage Photo Services

Luck also plays a part in old-house research. A newspaper article about one woman’s search for information about her house resulted in a call from an elderly man who had grown up in the house and had photos he was willing to share. This image revealed important clues to a missing porch railing.

Reviewing Biographical and Other Historical Resources

Your local library and historical society are also good places to look for biographical information on architects, builders, and previous owners. In addition to consulting the previously mentioned county histories for such information, consult biographical indexes for other leads. Ask for help in locating other useful resources—scrapbooks, diaries, memoirs, business and professional directories, church and club histories, and uncatalogued materials such as clipping files on architecture.

The Indiana Biography Index at the Indiana State Library includes statewide references to newspapers, periodicals, Who’s Who volumes, and other sources. If you suspect your house was built in the 1920s or 1930s you might find the name of the architect or builder in The Indiana Construction Recorder, another valuable resource in the Indiana State Library. Limited copies have been digitized. An Internet search of the title will link to digital collections.

The Indiana Historical Society Library also has resources that provide information on prominent citizens, businesses, neighborhoods and other topics. Numerous biographical sources have been digitized, including Men of Indiana in 1901, Indiana and Indianans, and Indianapolis Men of Affairs, 1923. Many blue books—“social directories” of the city—have been digitized, as well.

Examining Census Data

Beginning in 1850, census records include the names and number of people living in a house. In addition to revealing where inhabitants were born, their race, sex, age, and marital status, later records sometimes tell their occupations. Your local library or historical society may have census records, and many are available online free of charge or through subscription services such as Ancestry.com. The Genealogy Division of the Indiana State Library has several helpful links related to census records including a list of those available online.

Mining Additional Internet Resources

The number of historic digital resources available online increases daily. Indiana Memory, hosted by the Indiana State Library, is a collaborative effort of Indiana libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural institutions to share digital resources. Indiana Landmarks’ Historic Architectural Slide Collection, Wilbur D. Peat Collection, Historic Sites and Structures Inventories, and Indiana Preservation magazine are hosted by IUPUI and available through Indiana Memory.The Indiana Historical Society also maintains an outstanding digital image collection.

Don’t forget to check the blogs, Facebook pages and websites related to your home, neighborhood, and former residents. What Was There is an interactive way to see historic photos of your community and add your own images. Vintage Irvington is an excellent example of a blog that includes photographs and stories of this Indianapolis neighborhood. The Indiana Album is a collection of community-submitted visual records including many houses and buildings. Find a Grave can help locate biographical information, spouses names, and descendants.

Using Structural Clues

Your house itself can be a helpful part of your research. Its architectural style will provide clues to construction date and might document alterations and additions over time. Be sure to compare the current house plan with those seen on Sanborn Maps and Baist Atlases. Maps may reveal the addition or removal of porches or wings. For a quick guide to architectural styles in Indiana, check out On the Street Where You Live. A Field Guide to American Houses by Virginia Savage McAlester (Alfred A. Knopf publisher, 2013) provides a more in-depth resource on architectural styles, also including chapters on building forms and techniques that help to date houses.

Infrastructure development, such as sewers and electricity, provides further clues to architectural dates. Downtown Indianapolis had a sewer system established in the 1870s, but it quickly became inadequate. Significant improvements were made in a piecemeal fashion by 1925. Downtown Indianapolis had electricity for street lights in 1892, but still utilized gas for interiors. By 1912, most Indianapolis homes had electricity. Check with the local historical society or county historian for other areas.

If you are renovating your house, search for outlines that suggest former doorways or windows and check for differences in construction materials. Remember that original fabric may be hidden behind several layers. The United States government consolidated control of the American building industries during World War I, giving us standard lumber sizes. If the lumber used in your house is the true dimension—if your 2×4 is actually 2 inches by 4 inches—it should be pre-WWI. Plaster typically coated walls until after the 1950s.

Sample Research 3257 N. Pennsylvania

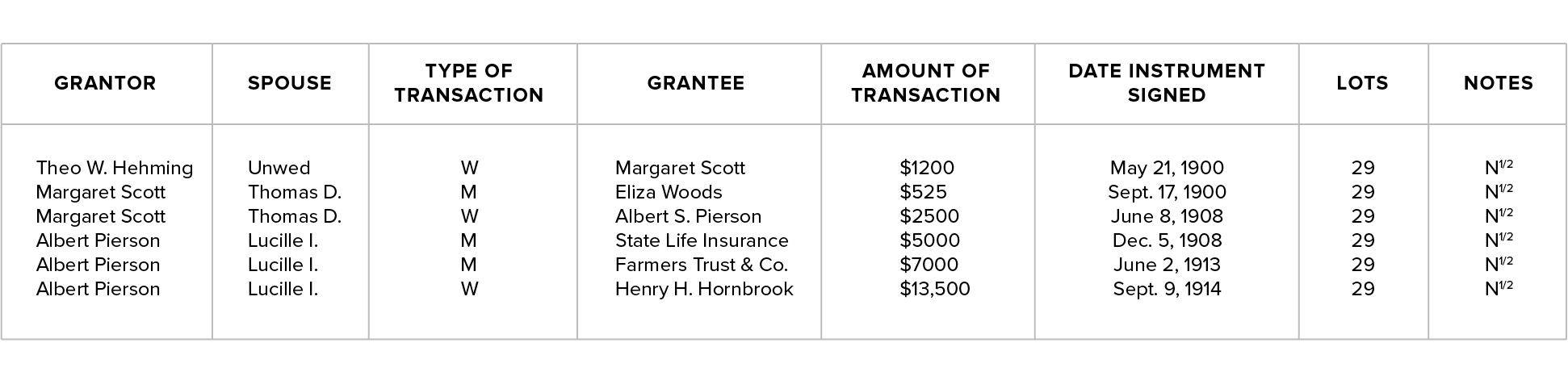

What does the chain of title tell us?

From the legal description, we know that our house includes only the north half of lot 29. The notation in the notes column confirms we have the correct property. In 1900 Theodore Helming sells the property (W=Warranty Deed) to Margaret Scott for $1200. Margaret gets a loan (M=Mortgage) from Eliza Woods for $525. $1200 is well below the price of a large house in 1900 so we can speculate that the lot is unimproved (no buildings). Margaret sells the property to Albert S. Pierson in 1909 for $2500–again, not enough for a lot and house. Albert takes out a $5000 mortgage from State Life Insurance. He also gets another mortgage in 1913 from Farmers Trust & Co. When Pierson sells the property to Henry Hornbrook in 1914, we see the price has jumped to $13,500, indicating a house very likely exists on the lot.

So how do we narrow the date of construction between 1908 and 1914? Let’s check other research sources.

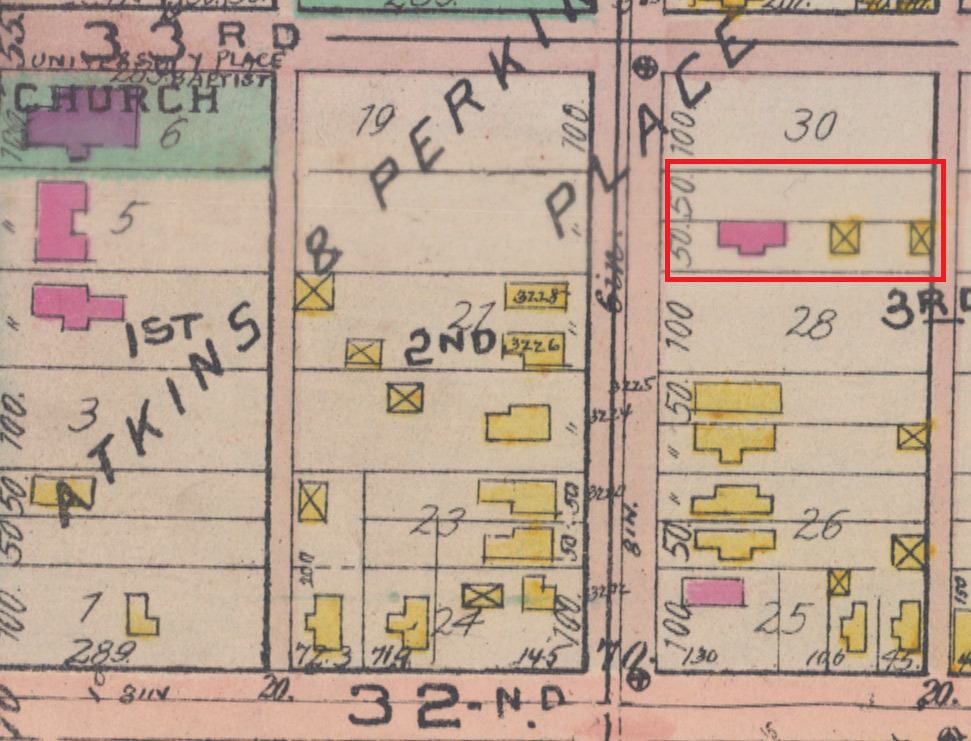

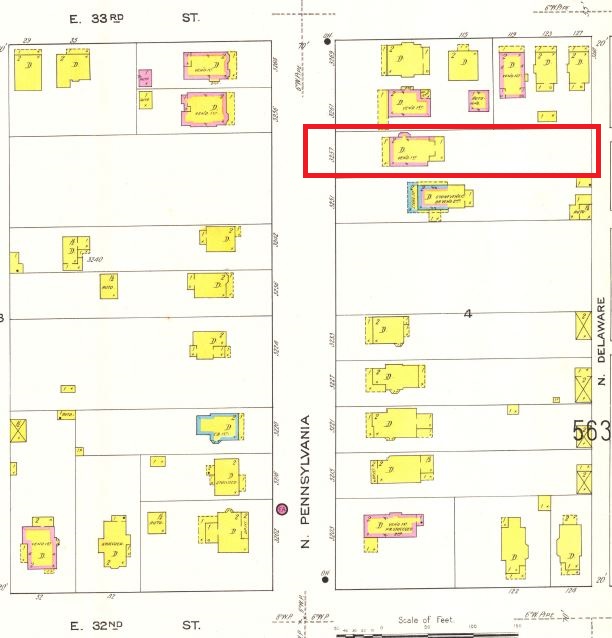

The earliest fire insurance map for this area is a 1908 Baist Atlas.

Credit: IUPUI University Library Center for Digital Scholarship Digital Collections

We see a house on this lot, but is it our house? It appears from this map that the lot has been divided and the existing house is on the south side of the lot. Our legal description is for the north side of the lot.

The next map available is the 1915 Sanborn Atlas. Here we see our property with the address 3257.

But the maps haven’t narrowed the gap between 1908 and 1914. Let’s check city directories.

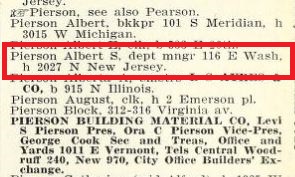

Credit: Indiana Landmarks Library

The 1908 Indianapolis City Directory lists Albert S. Pierson as a department manager working at 116 E. Washington Street and living (h=house) at 2027 North New Jersey.

The 1909 city directory shows Albert at the same work address, but his residence is now listed as 3239 North Pennsylvania. This does not match with our current address of 3257 North Pennsylvania. Since we know street addresses changed in 1916, this could still be the correct property.

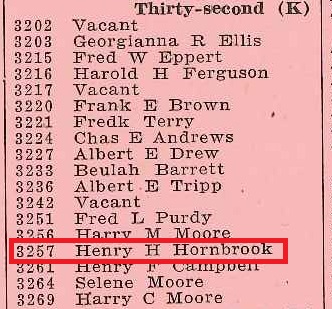

Credit: Indiana Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology

The 1916 City Directory shows Henry Hornbrook (the person who bought the property from Albert Pierson for $13,500 in 1914 as living at 3257 Pennsylvania. There is no listing for 3239 Pennsylvania. The street address changed.

Based upon our deed research, it’s possible that construction began in 1908. A story in the Indianapolis Star provides some missing details. An article appears on Sunday February 7, 1909, featuring “the attractive new home of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Pierson” at 3229 North Pennsylvania. The article contains a photograph that helps us further confirm that this is the house with a current address of 3257 North Pennsylvania. The article also shows a floor plan and provides detail on interior finishes. It is reasonable to assume that construction began on the property in 1908.

Biographical information found through Internet searches reveals that Albert S. Pierson was born in 1874. The 1911 Blue Book for Indianapolis lists him at 3239 North Pennsylvania Street and the 1921 Blue Book lists him as a Sergeant-at-Arms for the Rotary Club. An obituary shows that Henry Hornbrook died at his home at 3257 North Pennsylvania on September 20, 1935, at the age of 65. Hornbrook was an attorney and president of the Indianapolis Foundation. He graduated from DePauw and Harvard universities.

Keep in mind that not all house research is this straight forward. And while you may not find a feature newspaper article for your house, it’s possible you may find a small “for sale” advertisement. Remember that house research involves skill, luck, and most of all perseverance!

Helpful Websites

Association for Preservation Technology (APT) Building Technology Library

This site is a great resource for pre-1964 architectural trade catalogs, house plan books, and technical building guides.

Bureau of Land Management

Original federal land patents

Division of Historic Preservation & Archaeology

Information on National Register-listed properties, architectural surveys, and architectural style guide.

Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)

and SHAARD GIS.

Historic Preservation Commissions

For a list of Indiana Historic Preservation Commissions, check Indiana Landmarks’ Indiana Preservation Directory. The Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission has digitized a portion of its slide collection through the IUPUI Digital Library.

Indiana Album

A collection of community-submitted photographs, postcards, scrapbooks, and other pieces of ephemera and memorabilia related to Indiana history.

Indiana Landmarks

You’ll find links to the regional staff of Indiana Landmarks, one of whom covers your county and may be aware of the property you’re trying to research and the local sources who might be helpful. You may also find research assistance and information through Indiana Landmarks’ library.

Indiana Historical Society Library

Researchers can access Indiana newspapers for free by visiting the IHS Library. In addition to the newspaper database, the library provides free on-site access to several other online resources, including AncestryLibrary, Heritage Quest Online, American Civil War Database, etc.

The library also has excellent Digital Image Collections, including the Bass Collection, which focuses on Indianapolis. Local History Services provides a listing of local historical societies and county historians.

Indiana Memory

A collaborative effort of Indiana libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural institutions to share digital resources. This is one of the best places to start your online research.

Indiana Spatial Data Port of Indiana University

A list of Indiana Sanborn maps with digital access to pre-1923 copies.

Indiana State Archives and Indiana Digital Archives

In-house records include articles of incorporation and aerial photographs. Digital records include indexes to popular collections such as military, naturalization and court records, and photographs.

Indiana State Library

In-house resources include manuscripts, newspapers, county deed indexes, biographical sources, and clipping files. Digital resources include Hoosier State Chronicles, a rapidly growing free source of digital copies of historic Indiana newspapers, Indiana Biography Index, Indiana city directories guide, and county history holdings guide all of which may be accessed through the Indiana Collection homepage.

Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library

In-house resources include clipping flies, city directories, historic maps, and biographical resources. Digital collections include include postcards and the Indianapolis Star, 1903-1922 and 1991-present for library card holders.

IUPUI – University Library Digital Collections

Includes historic maps, photographs, city directories and local history resources with an Indianapolis focus.

Glossary of Commonly Used Land Research Terms

Grantee: The person to whom land ownership is transferred; the buyer

Grantor: The person who transfers property ownership; the seller

Mechanic’s Lien: A legal claim against a property for work performed but not paid. Commonly abbreviated “ML” or “Mech Lien.”

Mortgage Deed: A deed conveying property to a creditor as a security. Sometimes abbreviated “M” or “Mtg.”

Quitclaim Deed: A deed that conveys to the buyer only the seller’s interest. The buyer assumes responsibility for any claims brought against the property. Commonly abbreviated “QC.” A quitclaim is often used to transfer property to a family member.

Warranty Deed: A deed that includes a clause assuring the buyer that he/she owns the property free from interference by anyone making claim under a superior title. Commonly abbreviated “WD,” “W,” or “WAR.”

Indiana Landmarks

Indiana Landmarks Center

1201 Central Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46202

800-450-4534

317-639-4534

Email: sstanis@indianalandmarks.org

Central Regional Office, Indianapolis, 317-639-4534

Northern Regional Office, South Bend, 574-232-4534

Northeast Field Office, Wabash, 260-563-7094

Northwest Field Office, Gary-Miller Beach, 219-947-2657

Southern Regional Office, New Albany, 812-284-4534

Southeast Field Office, Aurora, 812-926-0983

Southwest Field Office, Evansville, 812-423-2988

Eastern Regional Office, Cambridge City, 765-478-3172

Western Regional Office, Terre Haute, 812-232-4534

Indiana Landmarks

Imagine the places that have meant the most in your life—your first school, the diner where you ate lunch with your mom, that barn, that bridge, the house where you grew up.

These are landmarks: the places that shape our lives and distinguish our communities. Indiana Landmarks saves and repurposes vintage places rather than throwing them away, to keep 3D connections to the past and to spare the landfills. We believe that, like hard work and hospitality, revitalization is a real Hoosier value.

We save landmarks because they improve property values, promote tourism, and inject vitality into neighborhoods and business districts. Most of all, Indiana Landmarks saves buildings because they make the places we live more beautiful, more interesting, singular and special. It’s our passion and our purpose. Won’t you join us?

Historic House Research Guide

Prepared by Indiana Landmarks and originally published as Indiana History Bulletin, Volume 64, Number 1, Winter 1993

Revised and reprinted by Indiana Landmarks, July 1997, and June 2016