NEWS

Bringing Attention to Evansville’s Black History

A new historical marker will help tell the story of Evansville’s Baptisttown neighborhood.

Hidden History

Historic places provide a tangible connection to those who came before us, along with opportunities for learning and reflection, fostering a sense of place, continuity, and communal identity. But in the case of Black heritage, often those buildings and artifacts simply don’t exist to help tell the story. In such cases, historical markers can serve as permanent visual representations to keep those connections alive. “Of course, preserving historic sites is our primary goal, but for Black history, many sites are no longer in existence,” says Eunice Trotter, director of Indiana Landmarks Black Heritage Preservation Program. “That is why historical markers are so important; they are often the only evidence of the history.”

In southwest Indiana, the program has helped fund several historical markers offering deeper insight into the area’s Black heritage. Most recently, the Indiana Historical Bureau approved a marker for Evansville’s Baptisttown neighborhood, which will be dedicated at the annual Baptisttown Emancipation Festival hosted by the Evansville African American Museum on Saturday, August 9 between 12:00-3:30 p.m. CST.

“Historical markers are important for preserving history and honoring the lives and legacies of those who came before us,” notes Tory Schendel-Vyvoda, Curator at the Evansville African American Museum. “With support from the Indiana Landmarks Black Heritage Preservation Program, we can work together to promote academic and civic engagement by enriching public spaces with Black narratives.”

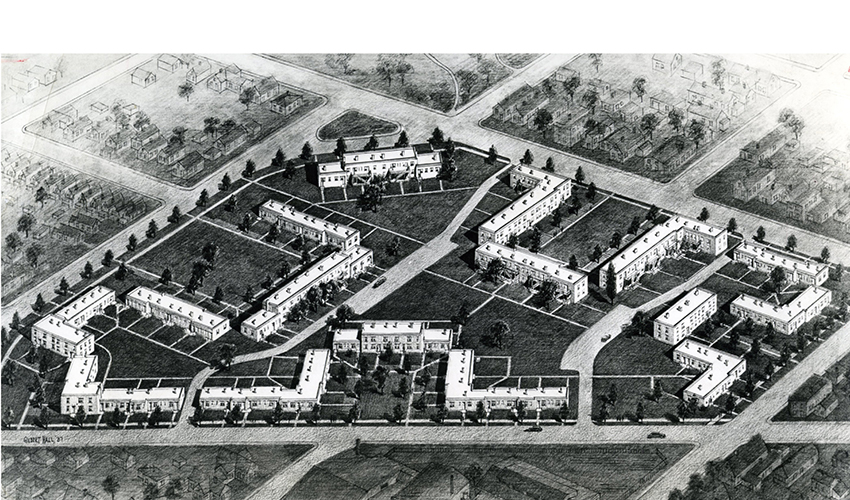

Baptisttown’s history can be traced back to the 1880s, when Evansville residents used the racially infused, stereotyped name to identify an area where African Americans settled around Governor and Canal streets and Lincoln Avenue. Over time, the Black community thrived, and its citizens claimed the name as part of the area’s identity. The neighborhood flourished between the 1930s and 1960s, with over 200 businesses, churches, social clubs and civic organizations. Today, the neighborhood’s Lincoln Elementary School, the former Black-only high school, and Liberty Baptist Church still stand as a connection to Baptisttown’s legacy, as well as a portion of the Lincoln Gardens housing development, now preserved as part of the Evansville African American Museum. Unfortunately, many of the places associated with the neighborhood no longer remain due to twentieth-century social-historical shifts including desegregation, heightened political tensions, and demolitions.

However, even as bricks-and-mortar landmarks are lost, dedicated efforts are ensuring the memory of these places remain. In addition to the historical marker that will stand in front of the Evansville African American Museum, Baptisttown’s history is being chronicled by the district’s listing in the National Register of Historic Places, a walking tour, and other efforts by the museum.

Indiana Landmarks Black Heritage Preservation Program works every day to preserve Black history before it is forgotten, even when those memories are difficult. The program is funding research for another historical marker commemorating African Americans that were horribly affected by medical experiments in Gibson County.

You can find more information about Baptisttown and the upcoming Emancipation Festival at evvaam.org. Discover other historical markers on the Indiana Historical Bureau website.

Stay up to date on the latest news, stories, and events from Indiana Landmarks, around the state or in your area.