NEWS

Road Tripping in the Era of the Green Book

Victor Hugo Green, Harlem postal worker turned travel agent, published the Negro Motorist Green Book from 1936-1967. The guide recommended businesses and attractions around the country, including sites in Indiana, that would be friendly to African American travelers.

Freedom (and Danger) on the Open Road

The rise of the automobile through the ’20s and ’30s in the United States granted Americans the opportunity to travel farther and on their own terms. This new found freedom, however, was not experienced by all. African Americans faced daily prejudice, and racial segregation amplified fears when they traveled to new places. Gas stations, hotels, and other service businesses that emerged to cater to automobile travelers, particularly after World War II, did not serve everyone. African Americans relied on word of mouth to know which local places to avoid, but information was more difficult to come by outside city limits and across state borders.

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

In response, Victor Hugo Green, a Harlem postal worker turned travel agent, created the Negro Motorist Green Book listing businesses safe for African Americans. Green adapted the idea from Jewish communities that created guides of businesses and places where Jewish travelers were welcome. Green’s first Green Book in 1936 covered only New York City, but its instant success prompted national expansion just a year later. At its height, nearly 15,000 books were printed, which according to the Introduction in the 1950 edition aimed to “give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.” In a letter to the editor in 1939, the author expressed that the book “will mean as much if not more to us as the AAA means to the white race.”

So, what was included in the book? Just like any good travel guide, the Green Book was packed full of business listings by city and practical advice for safe navigation on the road. Businesses included hotels, tourist homes, hotels, taverns, restaurants, garages, service stations, dance halls, theaters, barber shops, and beauty salons–places taken for granted by most travelers but cautiously approached by African Americans who preferred to patronize black businesses rather than risk unfriendly reception, rejection, or danger at white-owned establishments. Most editions also included advertisements for new cars and instructions on how to inspect your car, whether you were taking off for a cross country vacation or for a trip down state to visit family.

The Green Book in Indiana

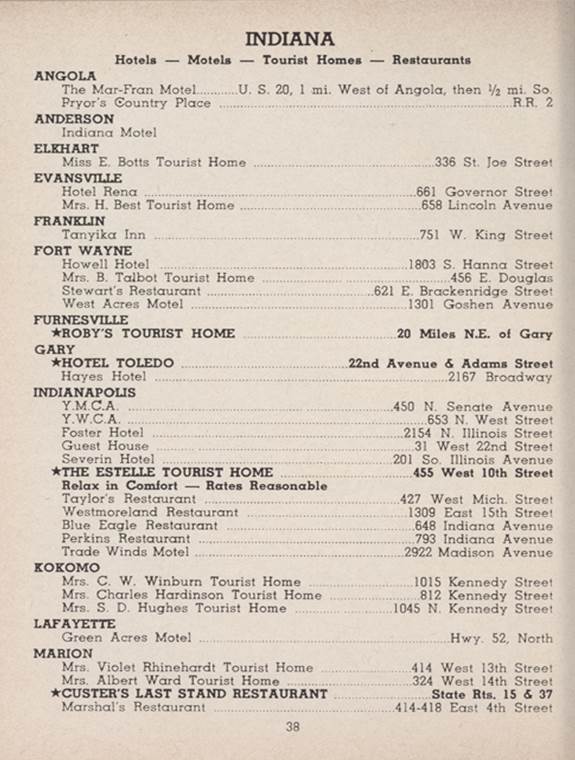

Over the three decades of its existence, the Green Book highlighted hundreds of places in Indiana in 17 different cities. Larger cities like Fort Wayne, Gary, Evansville, and Indianapolis had over 75 listings, while smaller cities like Kokomo, Elkhart, and Jeffersonville included only one or two safe stops. Cities naturally had more businesses and attracted more travelers, but they also had established African American communities where black-owned businesses thrived.

Sample of Indiana listings in the 1960 Green Book. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

One Green Book site of particular note for Indiana, Pryor’s Country Place in Angola was a vacation spot beginning in the ’20s and served African Americans from Indianapolis, Detroit, and Chicago. This inn on Fox Lake sits vacant on a large parcel of desirable land and made Landmark’s 10 Most Endangered list in 2016. Pryor’s serves as a reminder of the previous need for separate recreational spaces and a testament to the collective efforts of African Americans to pursue travel and leisure on their own terms.

Built in 1927 as a vacation home and later converted to an inn, Pryor’s Country Place in Angola provided lakeside accommodation and recreation to black vacationers. The rustic charm of the cobblestone and clapboard exterior conveyed a connection to nature.

Unfortunately, most of the storefronts, dance halls, and hotels that appeared in the Green Book over the years have vanished from the Indiana landscape. Following the triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement in the ’50s and ’60s, African Americans did not face as many barriers to their patronage in business and recreation, causing the number of black-owned businesses to dwindle. Urban renewal was also in full swing at this time, which in many communities led to demolition of predominantly African American commercial districts to make way for new highways and development.

Whether the businesses and attractions of the Green Book are standing or lost, the guide provides a unique perspective on what travel was like for African Americans from the ’30s to the ’60s. As we re-discover these locations in Indiana, we gain a deeper appreciation of our history.

You can view the Green Book for yourself online through the New York Public Library’s Digital Collection.

Stay up to date on the latest news, stories, and events from Indiana Landmarks, around the state or in your area.